Believe Against Myself

Ianko López

I consider myself a rational person, not very inclined to esotericism and magical thinking. As far back as I can remember, I am not a believer: I don´t think that there is more life but the one that goes between our birth and our death. If there was nothing before the first, nothing need to be after the second. And yet, existence seems to me unbearable, even preposterous, without a touch of mystery embedded in it. "Credo quia absurdum" ("I believe because it is absurd") stated - more or less, since it is a non literal quotation- Church father Tertullian in the 2nd century.

The tendency to believe in what we don't understand, in what doesn't make sense, paradoxically comforts us and settles us in the world, and it ends up becoming a necessity. Many people find religion the way to conduct it: after all, that's what religions are for. But in my case, art is what fulfills this function.

María Luisa Fernández Escultura roja “Cobarde temerario” 1989. Oil on wood - Galería Maisterravalbuena.

Not very long ago, the sculptress María Luisa Fernández, one of the Spanish contemporary artists that I most admire, told me during an interview: "I feel close to the idea of that magical process that is generated with images. Once, enjoying an exhibition by the photographer Virxilio Viéitez, and out of all logic, I felt an incredible emotion that wasn't present in the work of other authors of his generation with a very similar work. What is there in the work of Viéitez that it isn't in the others? What happens in two iron pieces of Richard Serra that doesn't happen in any other two iron pieces? I think art is conceptual and replete with symbols and information, but the operation that makes it special remains closer to magic than anything else." Although I concealed it as much as I could, I felt overwhelmed listening those words, which she pronounced without knowing that they represented with miraculous fidelity my own perception of the essence of art.

Anna Talens. “Stillleben”

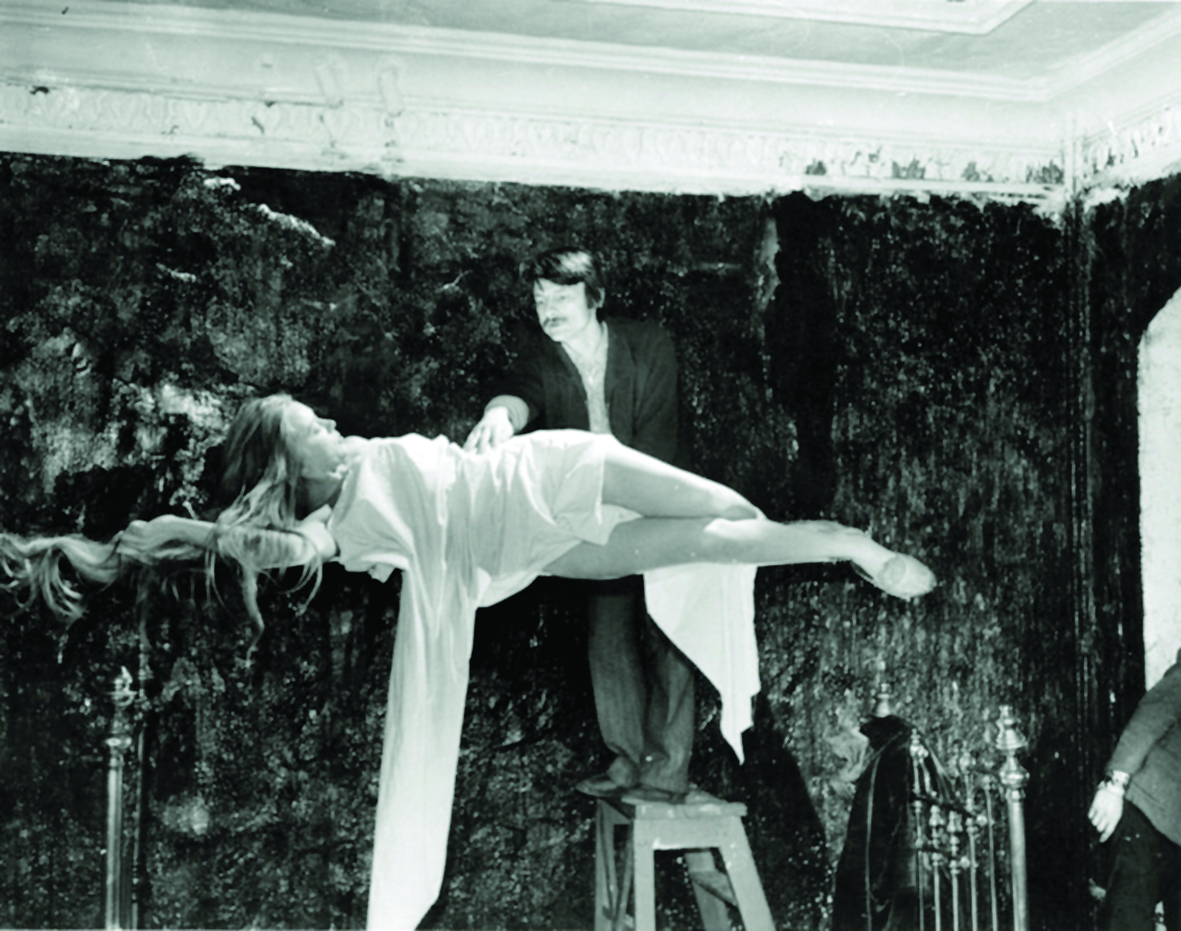

That perception had begun to take shape years before, while I watched "Andréi Rubliov" (1966), Andréi Tarkovsky's film, a story about the life of a painter of religious icons. This film contains a long sequence, indeed like a film inside the film, that meticulously documents the making of a huge bronze bell under the economic support of a prince in the medieval Russia. A boy named Boriska claims to be the only depository of the secret to cast bells, that his father, artisan of the guild, revealed to him before dying, and convinces the nobleman to hire him to run that endeavor. Thus, the young boy starts to lead a huge human team to which he gives instructions with superhuman security, sometimes contradictory, almost always despotic. When the bell is finished, conscious that the prince will demand his head if it doesn't sound right, Boriska falls apart and, in sobs, he admits that he is a fake: his father never revealed him his secrets, and all that time he had acted by pure intuition. However, the bell is raised and sound, and it sounds with as much power and harmony as the best bell ever made.

Andréi Tarkovsky "The mirror" (1975). Andréi Tarkovsky International Institute

In that scene-quite an autobiographical one, actually-Tarkovsky summed up his idea about art. He considered the creative process as a sort of possession through which the artist is not aware of the origin or destiny of the forces that guide him, but that end up generating its inexplicable and luminous outcome.

Anna Talens. “Stillleben”

Another contemporary artist, the Valencian Anna Talens, reminded me of that scene. In a meeting at the Spanish Academy in Rome, where she was a resident, she stated that as a creator she felt an instrument of a superior and unknown force, and that this mystery inevitably moves on to the material result of creation, to art itself.

I don't believe that behind all this there is an almighty deity or an eternal and immanent current. I suppose that it is rather a complex network of psychological processes that produces this work. And yet, against this assumption, against all logic and even against myself, I want to believe in the mystery and, therefore, I believe in it.

Because it is the minimum tribute to irrationality that saves me from being swallowed up by it: sometimes I seriously think that if art didn't exist I wouldn't have an escape from the threat of madness.